Adventure Drugs Rehabilitation ADR

Adventure therapy program for patients in rehabilitation for substance abuse

A Handbook for Addiction Counselors

Purpose of the handbook

This handbook has been written to provide to Addiction Counselors:

- an overview of the Adventure Therapy Methodology

- standardized processes to obtain appropriate, accurate and comprehensive information in order to facilitate the change process.

- recommendations on the implementation of the Adventure therapy Methodology in Addiction therapy.

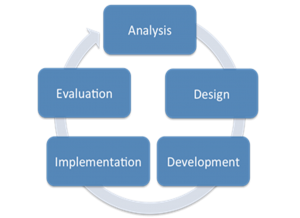

ADDIE Model

The Design of the Training Tool was based on the ADDIE model. The ADDIE model is a framework that lists generic processes that training developers use. It represents a guideline for building effective training tools in five phases.

Analysis phase

In the analysis phase, the project team clarified the objectives and identified the learning environment and the target population existing knowledge and skills. During the analysis, the objectives of the training tool were identified as well the needs of the target population, existing knowledge and any other relevant characteristics that help in better understanding.

The following questions were answered:

- Who are our target population and what are their characteristics?

- What are the related needs, behaviors, and motivations?

- What is the desired new behavior?

- What kinds of experiences do need?

- What related experience do they have?

- What do they need to know?

- What gap exists between what they know and what they need to know?

- What do we need to consider about them?

Design phase

In the design phase, the project team developed the learning objectives, assessment instruments, the exercises and their sequence, the setting, content and the final planning.

The following questions were answered:

- What content needs to be created?

- What appropriate activities need to be developed?

- Which are the goals?

- Ways to achieve the goals?

- What content consistent with the goals?

- What Protocol and Sequence of the activities?

- What learning theories will be used?

- What resources are available?

- Potential challenges?

Development phase

In the development phase, the project team created and assembled content features described in the design phase.

Implementation phase

During pilot implementation, the effectiveness of the training tool was applied and evaluated.

The following questions were answered:

- Can we deliver the pilot effectively and how?

- What content and resources will we need?

- How will we know if the pilot is has met the needs of the participants?

- What do they expect?

- What do they need?

- How can the pilot meet their needs?

- How can we help meet their needs?

- What do they need to know to accomplish the implementation?

- Who will support the pilot, how will be organized, where, when, etc.?

Evaluation phase

This phase refers to the design of the evaluation process of pilot implementation. The evaluation consisted of tests designed for criterion-related referenced items and providing opportunities for feedback from the participants.

The following questions were answered:

- Are the needs of participants being addressed in the design and development of the pilot?

- What methods are working/not working during the pilot?

- How did participants evaluate the tool upon completion?

- Which variables we will evaluate and evaluation tools we use?

What kinds of experiences do Drug Addicts need

Psychosocial interventions are structured psychological or social interventions used to address substance-related problems. They can be used at different stages of drug treatment to identify the problem, treat it and assist with social reintegration. Psychosocial interventions are used to treat many different types of drug problems and behavioural addictions. Clients are helped to recognize the triggers for substance use and learn strategies to handle those triggers. Treatment providers work to help patients to identify alternative thoughts to those that lead to their drug use, and thus facilitate their recovery. Psychosocial interventions can help drug users to identify their drug-related problems and make a commitment to change, help clients to follow the course of treatment and reinforce their achievements (Jhanjee, 2014; EMCDDA, 2016; Murthy, 2018).

Desired new behavior

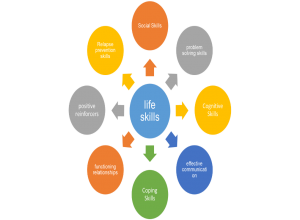

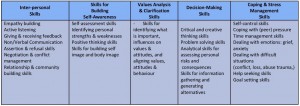

Life skills (decision-making and problem-solving skills, self-awareness, empathy, assertiveness, equanimity, resilience and general coping skills among others) are abilities that support the addicted person to adopt a positive attitude and enable him/her to effectively meet the demands and challenges of everyday life. The term “life skills” includes a cluster of cognitive, socio-psychological and interpersonal skills and behaviors that help an individual make informed decisions, communicate effectively and improve his/her interactive and self-managed skills and adopt an active, healthy lifestyle. Life skills can organize personal, interpersonal and environmental actions in a way that leads to better health, which in turn leads to more physical, psychological and social comfort. These skills allow the individual to accept the responsibilities of his social role and effectively address one’s own demands and expectations without harming him/ herself or others. Life skills training is a holistic approach to developing values, skills, and knowledge in persons, helping them to protect themselves and others in a number of risk situations.

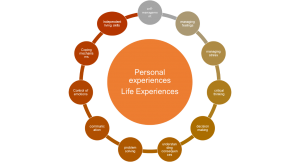

The purpose of life skills education

*Source (UNICEF. Life Skills-Based Education Drug Use Prevention Training Manual)

Life Skills and sub-skills in a drug use treatment program

*Source (UNICEF. Life Skills-Based Education Drug Use Prevention Training Manual)

How to achieve desired new behavior and the goals

Adventure Therapy

Adventure Therapy (AT) is used as a clinical tool to promote therapeutic changes to clients and has widespread use in a wide range of mental disorders either as a primary, complementary or parallel therapeutic tool. Is an active and experiential approach to group psychotherapy that uses outdoor activities as the main tool, utilizing real or perceived physical and psychological risk as clinically important factors in achieving desired change and goals. Is a program in which outdoor activities, which are physically and/or psychologically demanding, are used in a security and skills training framework to promote interpersonal and intrapersonal development. Adventure therapy is a form of experiential learning. Outdoor adventure activities are the primary practice of adventure therapy, while experiential learning methodologies guide its facilitation. As seen throughout this text, adventure-based outdoor activities have provided context for a diverse range of applications across the human experience. As such, the fundamental processes of designing and delivering adventure-based activities are fairly common regardless of their application or depth of intervention. Further, the concept and realities of experiential learning facilitation have played a central role in the development of these multiple expressions and manifestations of adventure programming (Luckner & Nadler, 1992; Gass, 1993; Ringer, 1994; Gass & Gillis, 1998; Alvarez & Stauffer, 2001; Fletcher & Hinkle, 2002; Russell, 2007; Gass, Gillis & Russell, 2012; Harper et al., 2014).

The common basis of Experiential Learning adds to the fact that in AT-programs there is a need for therapy, to begin with, and the program is designed to address this need. This might be different from other Experiential Learning or Experiential Education programs. In AT, participants come with a therapeutic question and want to address their problem within the context of an AT program. The program has to have a clear start and an end, depending on the needs of clients. There is a dynamic process going on between the identified needs and the program design (Adventure Therapy Europe, 2015)

Adventure therapy is practiced across the spectrum of public health, including in prevention, early intervention, treatment and continuing care for a range of health difficulties. Examples of the use of adventure therapy across this spectrum are provided (www.internationaladventuretherapy.org):

- Prevention – is keeping people healthy, well and connected

- Early intervention – is intervening early before the onset of a dysfunction, diagnosed difficulty, disorder or disconnection

- Treatment – is offering a tailored treatment for people with a known dysfunction, diagnosed difficulty, disorder or disconnection

- Continuing care – is helping people to maintain their health and wellbeing

Adventure Therapy Features

| Τherapeutic/counseling/ educational theories | Cognitive theory Reality theory Gestalt therapy Experiential education “learning by doing” Outdoor education |

| Basic elements | The positive effect of nature on the healing process The positive use of stress Active and direct involvement and responsibility of clients in their treatment Participating in adventure experiences that are meaningful to the client, particularly with regard to physical consequences Focusing on positive changes to current and future client behavior The use of unfamiliar experiences in nature and strong care and support embraced throughout the therapeutic experience. |

| Principles | The client becomes a participant and not a spectator in the treatment. Therapies require customers to create personal motivations in the form of energy, engagement and responsibility. Therapies are real and meaningful in terms of physical consequences for the client. Reflection is a crucial element of the healing process. Changes must have as much and future significance for customers and their society |

| Characteristics | Evaluating participants before adventure therapy Pre-activity discussion to prepare participants for personal change Activities selection to create personal change for participants The reflection phase to identify new experiences from participants and encourage their transfer to their everyday life. |

| Benefits | Active quintessence Experiential learning Call for action and encouragement of physical participation. In and out of therapeutic procedures. Creating a transfer of experience into everyday life Experiment with roles and archetypes. Our entire existence to “me in this state“ Nature and its properties as a screen. An alternative input to awareness. Treatment focuses on capabilities and forces rather than limitations and vulnerabilities. Actions have clearly visible consequences |

| Goals | Self-esteem Self-confidence Self – expressions Self-awareness Self-control Self-efficacy Goal setting Trust Self-critical thinking Abstinence focused strategies New Identity development Responsibility Therapeutic Alliance |

| Outcomes | Knowledge/awareness Personal growth/challenges Responsibility Relationships with others/teamwork Social Skill Acquisition Determination/ perseverance Physical fitness Transference Self s awareness/improvement/fulfillment Achievement of a personal goal Self-confidence/ esteem, sense of accomplishment Nature appreciation Development of Self-Concept Knowledge and Skills Realizations to Change Behavior Strengthened Family Relations Participation in the wilderness in the future Resiliency Impact on the attitudes of participants regarding their ideas of self and their connection to wilderness Increase self-efficacy and transference into the personal, social and work spheres of participants’ lives |

*Source (Gass, 1993; Ringer, 1994; Russell et al., 1999; Paxton & McAvoy, 2000; Fletcher & Hinkle, 2002; Goldenberg et al., 2005; Russell, 2007; Gass et al., 2012; Harper et al., 2014; www.aee.org)

Adventure therapy and addiction treatment

A broad range of therapeutic directions focuses their attention towards problematic behavior, the vulnerabilities of the client. However, alternative programs have proved to be successful for drug users and young offenders. Adventure therapy is an emerging therapeutic intervention in mental health practice to help individuals overcome emotional, addiction and psychological problems. In that frame, Adventure therapy activities provide an alternative way of addiction counseling: the alternative behavior can be the entrance and fuel the awareness of the meaning-making process. Instead of waiting for rational self-arguments or insights as to the necessary starting point for change, clients can begin experimenting with alternative behavior and trying out new things whilst being aware of the effect on themselves. In the adventure therapy approach, the attention and the perspective are placed on the present and in the future. It illuminates different ways to act and to engage the clients with all of their skills and abilities, with their limitations and taking into account their personal history, but focused on possibilities and strengths. There is a need to develop specialized adventure programs for substance users (Tobler, 1986; Gass & McPhee, 1990; Gillis & Simpson, 1991; Russell et al., 1999; Russell, 2007; Harper et al., 2007; Lewis, 2012; Bettmann et al., 2013).

Adventure therapy programs can:

- Be proposed and adopted as a cost-effective treatment for drug dependence

- Be proposed as an alternative for people who do not want to engage in traditional treatment

- Helps addicted people to understand the changes they need and want to do in their lives

- Gives a sense of accomplishment to the addict who is specific and real and who can use it in his everyday life.

- Manage negative emotions

- Increase their self-confidence

- Create a more favorable environment for staying in treatment

- Can help individuals develop strategies to deal with abstinence

- Adventure therapy leads to the assimilation of personal and interpersonal skills, such as communication skills, drug and alcohol awareness, and coping skills.

- The therapeutic benefits were not only sustained but continued to improve for a whole year after the intervention

- People who deal with problems with substance use are looking for these alternative treatment options by choosing something different from what traditional treatment offers them

*Source(Gass& McPhee, 1990)

*Source(Gass& McPhee, 1990)

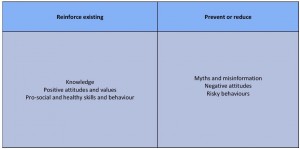

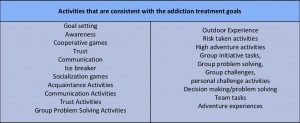

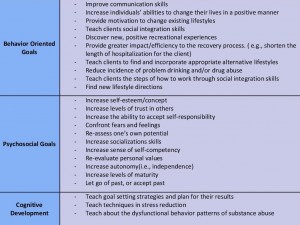

Identify and recognize specific behavioral, psychosocial and cognitive goals that we want to achieve through a treatment program. There is a need for (Gass & McPhee, 1990):

- Define a specific therapeutic approach for this population. The way an experience is acquired is important as it is associated with selecting a particular activity.

- Determine if adventure programs are inappropriate or negative treatment for specific individuals under particular circumstances. The adventure program has the potential to create positive changes.

- Determine whether a customer can participate in or be excluded from therapeutic adventures activities

Goals for Therapeutic Adventure Programs for Substance Abusers

*Source (Gass & McPhee, 1990)

Setting

Nature is a healing environment as it can provide natural challenges, offering benefits to both the physical and psychological condition of the individual. In nature, the person improves his / her self-confidence, regains a sense of calmness and makes thoughts that may lead to the discovery of a different new self. Adventure therapy usually takes place outdoors (Kaplan & Talbot, 1983; Miles, 1987; Fletcher & Hinkle, 2002).

Contact with nature has been shown to be a strong determinant of health, thereby justifying significant consideration in designing intervention strategies. Nature is a therapeutic environment as it can provide physical challenges for the person and offer both physical and psychological benefits improve cognitive functioning as interactions with nature can make a significant contribution to cognitive control. The individual can benefit from their experiences in the natural environment not only by restoring depleted resources but also by acquiring new skills. The individual improves self-confidence, regains a sense of calm, and makes thoughts that lead to a reflection that can lead to the discovery of a different young self who is less conflicted with less tension. (Kaplan & Talbot, 1983; Miles, 1987; Kaplan, 1995; Berman et al.,2008; Bowler et al., 2010; Hartig et al, 2010; Mitchell, 2013)

Nature restoration experiences can emerge as part of an intentional strategy for managing adaptive resources as well as incidentally, during their lives in an area close to nature. In this context, adventure therapy, which usually takes place outdoors is a type of program in which outdoor activities that are physically and/or psychologically demanding are used in a safety and skills training context to promote interpersonal and interpersonal development, utilizing a range of activities/experiences such as goal setting, awareness-raising, trust activities, group problem solving and individual problem solving (Luckner & Nadler, 1992; Fletcher & Hinkle, 2002; Hartig et al, 2010)

Nature can contribute to health in the following ways (Miles, 1987):

- In nature, the person is experiencing an inability to control the environment, which can help to cope with the stress of everyday life

- Limited environmental control in nature may lead to a reduction of forced control over other aspects of a person’s life, leading to a more relaxed and comfortable attitude

- Nature can help the individual to improve self-esteem and self-confidence

- In nature, the person improves the ability to learn through engagement with the environment

- Physical challenges can improve physical fitness

Benefits of Outdoor Adventure

*Source (Australian Outdoor Adventure Activity Benefits Catalogue, 2008)

Risk

Risk management relates to the perception of risk relative to the actual level of risk associated with a particular activity. With adventure experiences, with particular internal mechanisms, such as contrast and unknown knowledge, most people perceive adventure experiences as more dangerous than they actually are when they are involved. However, the activities must be “risky enough to provide an adventurous learning experience and engaging enough to challenge the participants, but appropriate to reduce the real risks they face”. The adventure involves both physical and emotional/psychological risks. Risk, both real and perceived, is an essential part of planning as it is essential to success. Risk-taking helps clients do something they believe they cannot achieve by transferring that attitude into their daily lives (Gall, 1987; Ewert, 1989; Priest, 1992; Priest & Gass, 1997; Fletcher & Hinkle, 2002;

Excessive risk = negative experience (Ewert, 1989)

The real risk exposes the client to possible damage, while the perceived risk is only an illusion of risk.

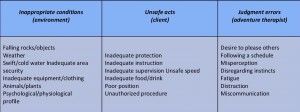

Examples of the Interacting Factors that Increase the Probability of Accidents in Adventure Activities.

*Source (Gass et al., 2012)

Processing

The processing is defined as the techniques used to increase the healing properties of the adventure experience based on an accurate assessment of the client’s needs. The treatment can occur before, during or after the adventure (Gass, 1993).

The processing activities can be used to (Gass, 1993a):

- help individuals concentrate or raise awareness prior to experience

- to facilitate awareness or to promote change while the experience is occurring

- to describe the experience after completion

- enhance change and incorporate it into the life of the participants after the end of the experience

Process learning Models

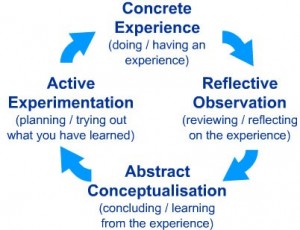

KOLB’S learning cycle model

The learning cycle basically involves four stages, namely: concrete learning, reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. Effective learning can be seen when the learner progresses through the cycle. The learner can also enter the cycle at any stage of the cycle with a logical sequence (www.simplypsychology.org).

- Concrete Experience – a new experience or situation is encountered, or a reinterpretation of existing experience.

- Reflective Observation of the new experience of particular importance are any inconsistencies between experience and understanding.

- Abstract Conceptualization – reflection gives rise to a new idea or a modification of an existing abstract concept.

- Active Experimentation – the learner applies them to the world around them to see what results.

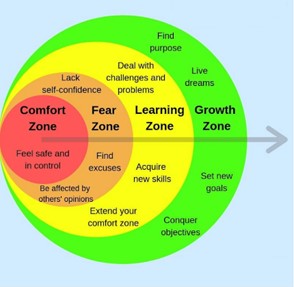

Comfort zone model

The comfort zone is a psychological state in which things feel familiar to a person and they are at ease and (perceive they are) in control of their environment, experiencing low levels of anxiety and stress. In this zone, a steady level of performance is possible.

- Think of some moment in which you felt some anxiety during the activity?

- What makes you feel at risk?

- How do you know that you were anxious? Where did you notice in your body?

- Where it was?

- Who did you be with? Or were you alone?

- What made you go from Learning zone to Panic Zone?

- What did you/others do to go to your Learning zone again?

- Do you feel your Center zone expanded after that experience? How?

- Tell 3 things that were obvious

- Tell 3 things that now you know were from your imagination

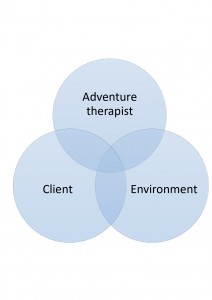

Professional adventure therapist/ Facilitator

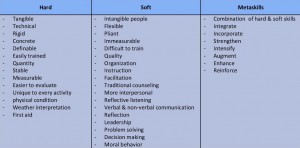

Participation in adventure therapy without education or training could have not only negative psychological effects but also possibly harmful physical effects on the clients. Must be professionally trained in both treatment and adventure planning as they should have both traditional counseling skills (soft skills) and additional skills such as outdoor sports management (hard skills) (Alvarez & Stauffer, 2001; Fletcher & Hinkle, 2002; Gass & Gillis, 2010; Gass Gillis & Russell, 2012; Tucker & Norton, 2013; Priest & Gass, 2018).

- Hard skills are solid, tangible, measurable, and often easier to assess. Hard skills for effective adventure therapist include technical activities, safety/risk, and environment.

- Soft skills are amorphous, intangible, difficult to measure, and often more difficult to assess. Soft skills for adventure therapist include organization, instruction, and facilitation.

The effective adventure therapist mortar, which cements everything together, is a mix of metaskills, those core competencies of a higher order that integrate with and potentiate the other skills (Priest & Gass, 2018).

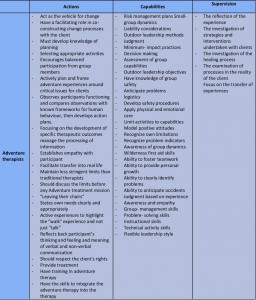

Adventure therapist/ Facilitator Skills

* Source (Priest & Gass, 1997; Fletcher & Hinkle, 2002; Tucker & Norton, 2013; Priest & Gass, 2018).

Adventure Therapist/ Facilitator features

*Source (Alvarez & Stauffer, 2001; Fletcher & Hinkle, 2002; Becker, 2010; Gass & Gillis, 2010; Gass Gillis & Russell, 2012; Tucker & Norton, 2013; Priest & Gass, 2018).

Adventure Therapist/Facilitator techniques

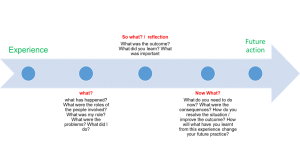

The Debriefing Process: What?, So What?, Now What?

The overall aim of debriefing is to give clients the opportunity to understand what happened to them and to connect and transfer these experiences to their daily lives.

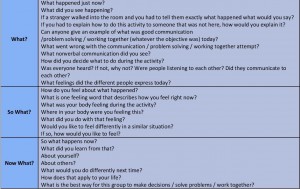

What?

Is the activity itself, a summary of what happened. The debrief focuses on the most recent activity. Ideally, more emotional or confrontational issues should be addressed in the later stages of the program, and so activities need to be sequenced to the physical and emotional needs and abilities of group members. Debriefing typically commences with questions concerning the “What?” as in “What happened in that activity?”. In this part of the debriefing, the facilitator encourages as many group members to provide their perception of the activity. This focuses on content about the experience rather than participants’ emotional responses (Reupert & Maybery, 2002; Lubans, 2009).

So what?

Is what you learned about yourself and others from the activity. Is focuses on the emotional meaning held by individuals as a result of what had previously taken place. The role of the facilitators is to encourage group members to describe the emotions that were generated as a result of what happened. This phase of the debrief attempts to link the emotional experience of group members to the content (the “What?”) and the subsequent roles played by individuals within the activity. Insights into group processes are heightened, and self-discovery maximized (Reupert & Maybery, 2002; Lubans, 2009).

Now What?

The third phase of the debrief, builds naturally from the “So What?”. Is what you derive—the takeaways—from the group activity to apply to your life and at work. Questions in this phase center on, “Now what will you do differently in the future?”. This becomes a goal setting exercise for both individuals and the group where intentions for behavior change are defined. Participants are encouraged to apply what has been learned to their relationships and lives outside of the program. This phase can also establish new ground rules (for the contract and the classroom) and initiate future activities that practice newly acquired group behavior (Reupert & Maybery, 2002; Lubans, 2009).

Examples of Debriefing Questions

*Source (Reupert & Maybery, 2002).

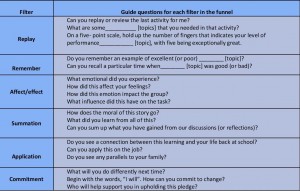

Funnel Model of Debriefing (Priest & Gass, 2018).

Replay

The replay question focuses the group on the topic or issue of interest-based on client needs, your program objectives, and any incidents that took place in the activity.

Remember

The remember question gets clients to identify an incident relating to the topic that took place during the experience. If you bring up the incident, the group may deny it or perhaps feel confronted. Therefore, you should ask a question that gets the group to bring up the issue, giving it ownership and control over the situation.

Affect and Effect

The affect/effect question addresses emotions and causes. Once clients bring up a specific incident related to an issue, you can ask other questions to ascertain the impact of that occurrence. These questions examine how each individual felt and how the group was influenced by the event

Summation

The summation question highlights new learning. Once you have ascertained the impact of the event, you ask clients to summarize what they have learned about the issue. So far, they have identified an occurrence and discussed its influence on their task performance and group dynamics.

Application

The application question helps establish linkages between the learning experience and real-life situations, thereby reinforcing learning and helping solidify its transference. Ask clients to make connections in the form of metaphors, or analogies, between the adventure and daily life.

Commitment

The commitment question looks toward change. Once clients have noted the usefulness of the new learning and how they might apply it in their daily lives, ask them to make a pledge and plan for action. You should press for answers in the form of an ‘I’ statement and get the group to support members who commit to doing things differently because of their guided reflection on the experience.

Funnel Guide questions

*Source (Priest & Gass, 2018).

Metaphor

Using objects, as symbolic representations of an experience, or personal attribute can be a very effective approach to processing. These activities engage participants in creating or choosing symbols representing a group success or individual strength or accomplishment. The strength of these types of activities is that they are not threatening to participants and facilitators, and leave the opportunities for creative and meaningful interpretation of experience wide open. Participants can attach their thoughts to a tangible object that they can touch and show to a group during group discussion or take away with them to represent their experience. This helps thoughts and ideas reach depth and character in a way that doesn‟t happen with dialogue alone. Because the participants can talk about the object or image rather than about themselves directly they sometimes express thoughts that otherwise would be left unsaid. Objects and images can be used to liven up the traditional sharing circle by providing interactive, kinesthetic ways to engage participants in group dialogue (Cummings, 2018).

Body Part Debrief

The Body Part Debrief activity is simple enough in nature that groups of any age will use it with ease. The body parts have a „coolness‟ factor to them that fosters a safe environment for people to talk. If you are having a hard time getting your participants to share or reflect, this activity will help solve that problem (Cummings, 2018).

| Eye | Could represent something new that you saw in yourself or someone else? What vision do you have for yourself/the group? What qualities do you see in yourself? How did you see yourself perform within the group? |

| Stomach | Could represent something that took guts for you to do. What pushed you outside your comfort zone? What sick feelings have you felt before? Was something hard to stomach for you? |

| Brain | Could represent something new that you learned about yourself, a teammate, or the group. What thoughts do you have? What did you learn through your experience? |

| Heart | Could represent a feeling that you experienced. What things come from the heart? What means a lot to you? |

| Hand | In what way did the group support you? Could represent someone you would like to give a hand to for a job well done. How did you lend a hand during the activity? |

| Ear | Could represent something you listened to. What was a good idea you heard? Could represent something that was hard to hear—did you receive constructive feedback or not-so-constructive feedback. |

Programming

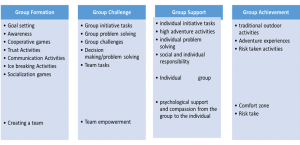

Programming in adventure therapy involves:

- a planning process taking into account factors such as

- the emotional maturity of clients

- levels of physical skills

- social development

- cognitive abilities

- any mental or physical disabilities

- a complete assessment and diagnosis of the needs of the client or group

Aiming at the selection of activities by the therapist, thus creating the right conditions for change

When designing and selecting adventure activities, the therapist should focus not only on the clinical objectives of the clients or the team but also on the emotional and physical safety of the clients, which is a unique aspect of this type of active intervention (Tucker, 2009).

Careful analysis of activities toward treatment goals requires the ability to assess the needs of the client or group as well as an understanding of the activities selected for these specific goals (Tucker & Norton, 2013).

The adventure therapy utilizes a range of activities/experiences such as goal setting, awareness, confidence activities, individual and team problem solving, processing and transfer (Luckner & Nadler, 1992).

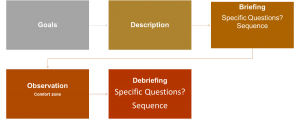

Adventure Therapy activities

This section introduces activities as the primary mode of intervention and the primary catalyst for change in adventure therapy (www.aee.org).

Cooperative Activities

Cooperative activities involve interaction between clients and practitioners that require clients to engage with others for mutual benefit toward the development of therapeutic outcomes. Cooperative activities are often designed by the practitioner with the intention of creating positive interaction and fun. It is important to draw a distinction between games and activities. Games are playful and without expectation for change in a person. Activities, in this context, are chosen specifically for the clientele and with therapeutic intent (www.aee.org).

Trust and Support Activities

Trust and support activities involve the creation of an experience in which the client is not in total control and is required to count on other people to accomplish the task presented. It also provides opportunities for clients to be in a position where they provide physical and emotional support and have a level of control over someone’s physical safety and emotional well-being (www.aee.org).

Initiative Activities

In the context of treatment, initiative activities aim to engage participants in the initiation of emotional or behavioral

High Adventure/Natural Environment Activities

Activities in this section are challenging to categorize for their diversity, both in terms of the activity itself as well as the length of time the activities may occur. Activities discussed here include overnight camping, backpacking, rafting, kayaking, hiking, mountain biking, rock climbing, caving and various other outdoor pursuits. These activities can occur in a day, a weekend, or as part of an extended expedition trip (www.aee.org).

Natural environment or low adventure activities have decreased risks and minimal requirements for skills development. The duration may be shorter and may not require advanced skills to be completed successfully. Examples include hiking, creeking, fishing, or paddling on flat water in a controlled environment. In these activities, it is still critical to remain aware that the activity may seem to be low intensity for the practitioner, but may, in fact, be a high-intensity experience for the client (www.aee.org).

Adventure Therapy activities

*Source (www.aee.org)

*Source (www.aee.org)

Matching the Activity to Client Needs (www.aee.org)

Clinical Goals

Every decision must be related to the clinical goals of your client.

Client Interests, Strengths, and Limitations

A practitioner can greatly influence client engagement, level of involvement, and transferability of activity by applying the practitioner’s understanding of a client’s interests and strengths to the activities used and how the practitioner decides to facilitate them. Practitioners select activities that are achievable for clients.

Client Development

Consider the stage of the client in the change process, the developmental stage of the client or group development.

Sequencing

Activities are selected in a sequence that supports the client’s progress toward goals.

Activity Structure

Consider what is required of a client to successfully complete an activity. It is often helpful to create a parallel process so what is required to complete the activity successfully is the same things that will be required to achieve the treatment goals.

Activity Presentation and Props

Assess and attend carefully to the expected implications of the props presented and use them intentionally to enhance the experience. Rules, guidelines, safety considerations, space, and time are all issues that you can adapt to meet the needs of your clients.

Level of Risk

Adapt activities to compensate for what you are seeing in clients related to physical safety and emotional risk.

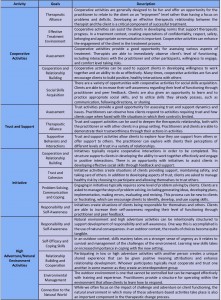

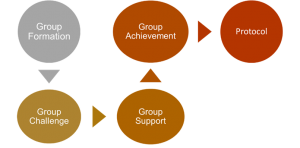

The sequence of the activities

Group Formation

All of the activities used at the beginning of the prescribed sequences are designed to help the members of a new group get acquainted with each other. Their progressive set of activities allows the participants to experience fun in a safe social environment. In addition, some of the initial activities are purposefully designed to develop trust and communication skills among participants.

Group Challenge

All of the activities are used to expose the group with physical or mental challenges. To resolve these challenges, the group must make decisions while cooperatively recognizing the need for leadership and followership.

Group Support.

These categories of activities are quite similar because they require not only self-confidence and determination from the participant, but also psychological support and compassion on the group’s part

Group Achievement.

The final phase represents the category of activities that extends the adventure into the realm of traditional outdoor pursuit activities. This may include short-term canoeing, backpacking, and/or mountaineering expeditions etc. The categories are titled adventure experiences, adventure activities, and activity-based or wilderness-based pursuit’s activities. These activities require more time and commitment from the participants and they are invariably placed at the end of the experience.

Activities protocol

Recommendation for implementation

Guidelines for Activities in Adventure Therapy (www.aee.org)

- Be competent in the activities being used by the facilitator. If the facilitator is not fully competent, he or she must be paired with someone who is fully competent in the areas required

- Utilize appropriate risk management and safety guidelines, taking into consideration the special issues presented with varying treatment populations.

- Actively involve clients in the activity. Utilize behavior that is not within expectation as part of future interventions. Understand that completion of the activity is secondary to the learning through the activity.

- Be aware of client cultural beliefs and values about working with others, managing emotions, solving problems, dealing with conflict, touch, and personal expression

- Select activities that are appropriate to the client’s level of functioning and the ongoing assessment related to level of challenge, perceived risk, actual risk, knowledge of and relationship with the client

- Understand how to adapt and modify activities to best meet the client’s particular developmental position, therapeutic goals, and other dynamics that affect the choice of an activity

- Teach, reinforce, and monitor for physical and emotional safety

- Monitor components of assessment continuously, including emotional and behavioral responses to interventions, perceived and actual risk, safety, progress toward treatment goals, and client functioning

- Create an optimum learning environment based on assessment

- Facilitation should reference therapeutic intent and connect to related life experiences. Client emotional and behavioral responses are related to treatment goals in order to enhance the transfer of learning

- Maintain awareness of real and perceived risk. Adventure therapy contains aspects of real and perceived risks that impact clients.

Risk Management in Adventure Therapy (www.aee.org)

- It is of paramount importance for AT facilitator to have established risk management plans in place that reduce the potential for causing trauma to clients.

- AT facilitator need to have a clear idea of the severity of client issues that can be managed by the services provided and follow identified criteria in making these clinical decisions. If a client presents a significant risk of harm to self or others, program removal must be considered.

- AT facilitator must assess clients and facilitate activities carefully so that risk is managed and clients are compliant at an acceptable level.

Clinical Quality Assurances (www.aee.org)

- Assessment: Initial assessments regarding client appropriateness for services.

- Treatment Planning: Appropriate and effective treatment plans are to be developed with clients that indicate the frequency and duration of interventions for clearly identified problems.

- Clinical Documentation: Documentation is to be completed completely, professionally and in a timely manner. Documentation will likely include assessments, treatment plans, progress notes, and incident reports.

- Informed Consent: Practitioners are expected to communicate clearly and openly with clients about the risks and benefits.

- Confidentiality: In providing AT, it is expected for organizations, programs, and practitioners to inform clients about their level of confidentiality and the limits of confidentiality.

- Program Evaluation: The effectiveness of services is evaluated in order to determine if the services are meeting designated goals.

Recommendations

- Production of “eustress” as a motivational agent for change (Gillis & Gass, 2004).

When properly implemented, adventure experiences introduce eustress, or the healthy use of stress, into the group member’s system in a manageable yet challenging manner. This type of stress places individuals into situations where the use of certain positive problem-solving abilities (e.g., trust, cooperation, clear and effective communication) is necessary to reach a desired state of equilibrium.

- Solution-oriented structures (Gillis & Gass, 2004)

Entering therapy can be extremely threatening, heightening client defense mechanisms and resistance to change. Most adventure experiences possess the natural occurrence of solutions in their structure. With unfamiliar adventure experiences, group members are presented with opportunities to focus on their abilities rather than on their dysfunctions.

- Changes in the therapist’s role (Gillis & Gass, 2004).

Adventure therapy experiences change the role of therapists from passive and stationery to more active and mobile. Therapists are encouraged to actively design and frame adventure experiences around critical issues for group members, focusing on the development of specific treatment outcomes.

- Conflict resolution patterns to structurally implement change (Gillis & Gass, 2004).

Adventure experiences are usually designed with internal mechanisms of resolvable conflict.

- Create and Maintain a ‘Reflective Space (Peeters, 2003)’.

- Facilitate the ‘Here and Now’ Experiencing the Participants (Peeters, 2003).

- Heighten the interpersonal safety of the relationship (Peeters, 2003)

- Focus to actual features of the experience (Peeters, 2003)

- Try to avoid descriptions or names that narrow or devaluate the proper experience of the participant (Peeters, 2003)

- Encourage participants to directly contact what is anxiety-provoking and was previously avoided (Peeters, 2003).

- Set up and personalize activities to generate new experiments (Peeters, 2003)

- Program development needed to be detailed and conducted in consultation with the treatment plan of the clients.

- The transition planning, after the adventure therapy intervention, in addiction therapy is important in order to assist clients to apply the outcomes in their everyday life.

- Identification of high-risk clients and levels of activity for clients on medications.

Useful

- Develop an itinerary as a map so you can plan your meals, activities and prepare the equipment you use. In addition, also designed an alternative in case of unexpected events. Also Determine the Distance, the terrain and the weather conditions

- Outline a full description of the route you want to follow, where you intend to camp and when to return. A travel plan will help your partners know where you are going and when you plan to return.

- Determine the location of the nearest medical facility and how to evacuate an injured member.

- Operate within your training and abilities.

- Determine the appropriate team Size and the member Capabilities regarding high-adventure trek or any outdoor adventure

Policy Recommendations

Adventure therapy is an intervention shown to be effective with this specific population. Implementing interventions and programs with proven efficacy can give drug addiction organizations the opportunity to provide more effective treatment as effective interventions and procedures can improve chances of their clients to improve their psychosocial outcomes, reducing relapse by requiring fewer treatment cycles.

Implementing innovative interventions involves the entire organization. Involving staff in the process can enhance motivation and encourage staff members and make them feel better about their work. In that framework, it is suggested that training opportunities on adventure therapy methodology, must be provided for staff working in the addiction field in order to enhance the capacity building and acquire the necessary skills and knowledge aiming of building confidence in the application of this method.

The training should include: (a) the theory developed in the field of adventure therapy. (b) the development of the skills to apply the principles of adventure therapy (planning, process, risk management, etc.) (c) how to linking and applying adventure therapy to addiction therapy. This training could be conducted by inviting experts in the field of adventure therapy and provision of literature in these areas.

Download the Handbook here:

Handbook- Adventure Drugs Rehabilitation

References

- Adventure Therapy Europe (2015). “Reaching for Roots and Finding a Forest”. REACHING FURTHER

- Alvarez, A. G., & Stauffer, G. A. (2001). Musings on adventure therapy. The Journal of Experiential Education, 24(2), 85–91.

- American Society of Addiction Medicine (2011). Public Policy Statement: Definition of Addiction

- Australian Outdoor Adventure Activity Benefits Catalogue (2008). Centre for Tourism Research, University of Canberra

- Becker, S.P. (2010). Wilderness Therapy: Ethical Considerations for Mental Health Professionals. Child Youth Care Forum 39: 47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-009-9085-7

- Bettmann J. E., Russell C. K. & Parry J. K., (2013). How Substance Abuse Recovery Skills, Readiness to Change and Symptom Reduction Impact Change Processes in Wilderness Therapy Participants. Journal of Child and Family Studies, Volume 22, Issue 8, pages 1039–1050

- Bisson, C (1998). Sequencing Adventure Activities: A New Perspective. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Association for Experiential Education

- Bowen, Daniel & Neill, James. (2013). A Meta-Analysis of Adventure Therapy Outcomes and Moderators. The Open Psychology Journal. 6. 10.2174/1874350120130802001.

- Bowen, Daniel, Neill, James, R. Williams, Ian & Mak, Anita & Allen, Nicholas & Olsson, Craig. (2016). A Profile of Outdoor Adventure Interventions for Young People in Australia. Journal of Outdoor Recreation, Education, and Leadership. 8. 10.18666/JOREL-2016-V8-I1-7281.

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (2004). Substance Abuse Treatment and Family Therapy. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 39. DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 05-4006. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

- Cummings M (2018). Effective Debriefing Tools and Techniques

- EMCDDA / Robert West (2013). Models of addiction

- EMCDDA, (2016). The role of psychosocial interventions in drug treatment (Perspectives on drugs)

- Ewert, A. W. (1989). Outdoor adventure pursuits: Foundations, models, and theories. Columbus, OH: Publishing Horizons.

- Fletcher, T. B. and Hinkle, J. S. (2002). Adventure Based Counseling: An Innovation in Counseling. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80: 277-285.

- Gall, A. L. (1987). You can take the manager out of the woods, but…Training and Development Journal, 41, 54–58

- Gass, M. A. & Gillis, H. L. (1998). A room with a view: Adventure therapy programs in traditional office settings. Paper presented at the Association for Experiential Education 26th Annual International Conference, Lake Tahoe, Nevada.

- Gass, M. A. & Gillis, H. L. (2010). ENHANCES: Adventure therapy supervision. Journal of Experiential Education, 33 (1), 72-89.

- Gass, M. A. (1993a). The evolution of processing adventure therapy experiences. In Gass, M. A. (Ed.). Adventure therapy: Therapeutic applications of adventure programming, (pp. 219— 229). Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

- Gass, M. A. (1993b). Enhancing metaphor development in adventure therapy programs. In Gass, M. A. (Ed.). Adventure therapy: Therapeutic applications of adventure programming, (pp. 248-258). Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

- Gass, M. A., & Gillis, H. L. (1995). CHANGES: An assessment model using adventure experiences. Journal of Experiential Education, 18(1), 34–40.

- Gass, M. A., Gillis, H. L., & Russell, K. C. (2012). Adventure therapy: Theory, research, and practice. New York: Routledge.

- Gass, M.A. (Ed.). (1993). Adventure Therapy: Therapeutic applications of adventure programming. Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing Company

- Gass, Michael & J. Mc Phee, Pamela. (1990). Emerging for Recovery: A Descriptive Analysis of Adventure Therapy for Substance Abusers. Journal of Experiential Education. 13. 10.1177/105382599001300206.

- Gillis L. H. & Gass A. M (2004). Adventure therapy with groups

- Gillis L. H. & Simpson C., (1991). Project Choices: Adventure‐Based Residential Drug Treatment for Court‐Referred Youth. By: H. L. Lee Gillis Cindy Simpson. In: Journal of Addictions & Offender Counseling, volume 12, pages 12-27

- Gillis, H. & Gass, M. (2004). Adventure therapy with groups. In J. L. DeLucia-WaackD. A. Gerrity & C. R. Kalodner Handbook of group counseling and psychotherapy (pp. 593-606). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications

- Gillis, H. L, & Thomsen, D. (1996). A research update (1992-1995) of adventure therapy: Challenge activities and ropes courses, wilderness expeditions, & residential camping programs.

- Gillis, H. L. (1995). If I conduct outdoor pursuits with clinical populations, am I an adventure therapist? Leisurability, 22, (2), 5-15.

- Gillis, H. L., Gass, M. A., Bandoroff, S., Rudolph, S., Clapp, C., and Nadler, R. (1991). Family adventure survey: Results and discussion. In C. Birmingham (Ed.), Proceedings Journal of the 19th Annual AEE Conference (pp. 29-39). Boulder, CO: Association for Experiential Education.

- Goldenberg, M., McAvoy, L., & Klenosky, D. (2005). Outcomes from the components of an Outward Bound experience. Journal of Experiential Education, 28(2), 123-146.

- Harper, N. J., Peeters, L, & Carpenter, C. (2014). Adventure Therapy. In R. Black & K. Bricker (Eds). Adventure Programming and Travel for the 21st Century. Venture Publishing.

- Harper, N., Russell, K., Cooley, R., & Cupples, J. (2007). Catherine freer wilderness therapy expeditions: An exploratory case study of adolescent wilderness therapy, family functioning, and the maintenance of change. Child & Youth Care Forum, 36,111–129. doi:10.1007/s10566-007-9035-1.

- Itin M C. (2001). Adventure Therapy–Critical Questions. Journal of Experiential Education , v24 n2 p80-84

- Jhanjee S. (2014). Evidence based psychosocial interventions in substance use. Indian journal of psychological medicine, 36(2), 112–118. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.130960

- Kaplan, S., & Talbot, J. F. (1983). Psychological benefits of wilderness experience. In M. A. Gass, Adventure therapy: Therapeutic applications of adventure programming (pp. 44–46). Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

- Kolb A. D., (1980). Experiential Learning: Experience As The Source Of Learning And Development

- Lewis F. S., (2012). Examining changes in substance use and conduct problems among treatment‐seeking adolescents. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, volume 18, issue 1, pages 33-38

- Lubans J. Jr. (2009). What? So What? Now What?. Library Leadership & Management

- Luckner, J. L., & Nadler, R. S. (1992). Processing the experience: Strategies to enhance and generalize learning. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

- McKenzie, Marcia. (2000). How are Adventure Education Program Outcomes Achieved?: A Review of the Literature. Australian Journal of Outdoor Education. 5. 10.1007/BF03400637.

- McLeod, S. A. (2017). Kolb – learning styles. Retrieved from simplypsychology.org/learning-kolb.html

- Miles, J. C. (1987) Wilderness as a healing place. Journal of Experiential Education, 10, 4–10.

- Murthy P. (2018). Guidelines for psychosocial interventions in addictive disorders in India: An introduction and overview. Indian journal of psychiatry, 60(Suppl 4), S433–S439. doi:10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_35_18

- Nadler, R. S. & Luckner, J. L. (1992). Processing the adventure experience. Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing. pp. 3-6

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (2018). Drugs, Brains, and Behavior. The Science of Addiction

- Norton, C. L., & Tucker, A. R. (2010). New heights: Adventure-based groupwork in social work education and practice. Groupwork, 20(2), 24–44. doi: 10.1921/095182410X551694.

- Paxton, T., & Mc Avoy, L. (2000). Social psychological benefits of a wilderness adventure program. In S. McCool, D. Cole, W. Borrie, & J. O’Loughlin (comps.) Wilderness science in a time of change conference, 3, 202-206; May 23-27 1999; Missuola, MT.

- PEETERS, L. (2003). From Adventure to Therapy: Some necessary conditions to enhance the therapeutic outcomes of adventure programming. In: K. Richards & B. Smith (eds.) Therapy within Adventure, Proceedings of the Second International Therapy Conference, (pp. 127-138), Augsburg, ZIEL.

- Priest S. & Gass A. M., (2018). Effective Leadership in Adventure Programming

- Priest, S. & Gass, M. (1997). Effective leadership in adventure programming. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Priest, S. & Gass, M. (2018). Effective leadership in adventure programmi 3d Edition.

- Priest, S. (1992). Factor exploration and confirmation for the dimensions of an adventure experience. Journal of Leisure Research, 24, 127–139.

- Reupert E. A. & Maybery D. (2002). Debriefing Strategies in Adventure Based Counselling. Australian Journal of Guidance & Counselling, Volume 12, pp. 107-117

- Richards, G.E., & Neill, J.T. (1994). An introduction to the Participant’s Evaluation of Program & Instructor Quality (PEIPQ-B).

- Ringer, M. (1994). Adventure as Therapy: A Map of the Field. Workshop Report. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No.

- Russell, K. C, & Gillis, H. L. (2017). The adventure therapy experience scale (ATES): The psychometric properties of a scale to measure the unique factors moderating an adventure therapy experience.

- Russell, K. C. (2007). Adolescent substance-use treatment: Service delivery, research on effectiveness, and emerging treatment alternatives. Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 2, 68–96.

- Russell, K. C., Hendee, J. C., and Phillips-Miller, D. (1999). How Wilderness Therapy Works: An Examination of the Wilderness Therapy Process to Treat Adolescents with Behavioral Problems and Addictions. In: Cole, D. N.; McCool, S. F. 2000. Proceedings: Wilderness Science in a Time of Change. Proc. RMRS-P-000. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station.

- Sussman S. & Sussman N. A (2011). Considering the Definition of Addiction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 8(10):4025-38.

- Tobler, N. S. (1986). Meta-analysis of 143 drug prevention programs. Quantitative outcome results of program participants compared to a control or comparison group. Journal of Drug Issues, 56, 537-568.

- Tucker, A. R. & Norton, L. C. (2013). The Use of Adventure Therapy Techniques by Clinical Social Workers: Implications for Practice and Training. Clinical Social Work Journal 41:333–343

- Tucker, A. R. (2009). Adventure-based group therapy to promote social skills in adolescents. Social Work with Groups, 32(4), 315–329. doi:10.1080/01609510902874594

- Life Skills-Based Education Drug Use Prevention Training Manual,

- Watkins K. (2014). Adventure Based Counseling – Experiential Activities, NASAP Conference handouts

- drugabuse.gov

- who.int

- emcdda.europa.eu

- aee.org

- internationaladventuretherapy.org

- adventuretherapy.eu

- simplypsychology.org

- training-wheels.com

- ultimatecampresource.com

- reviewing.co.uk